My story

Why accidental conservationist?

Though it took me nearly 40 years to figure out, my vocation is the somewhat obscure Science and Technology Policy field. My calling as a conservation technologist found me. I can’t say that I thought much about conservation or wildlife well into my career - certainly no more than the average person watching an occasional wildlife documentary. I started my career as a computer engineer. Those who know me know that sitting quietly behind a computer screen writing code is not something I’m particularly well suited to do, not my vocation.

The journey from being an engineer at large and small for-profit companies to leading conservation technology programs was far from a straight line. It started by getting out from behind the desk and living in Sweden and Germany, following a desire to work in places and with people from other cultures speaking languages other than English. Along the way, I added a German Language and Literature degree to my engineering degree. While I felt I had taken steps towards doing more fulfilling work, the products I worked on weren’t solving the problems I cared about. As I evaluated “what next” in the wake of the dot com bust of the early 2000s, I learned about the field of science and technology policy - and wicked problems.

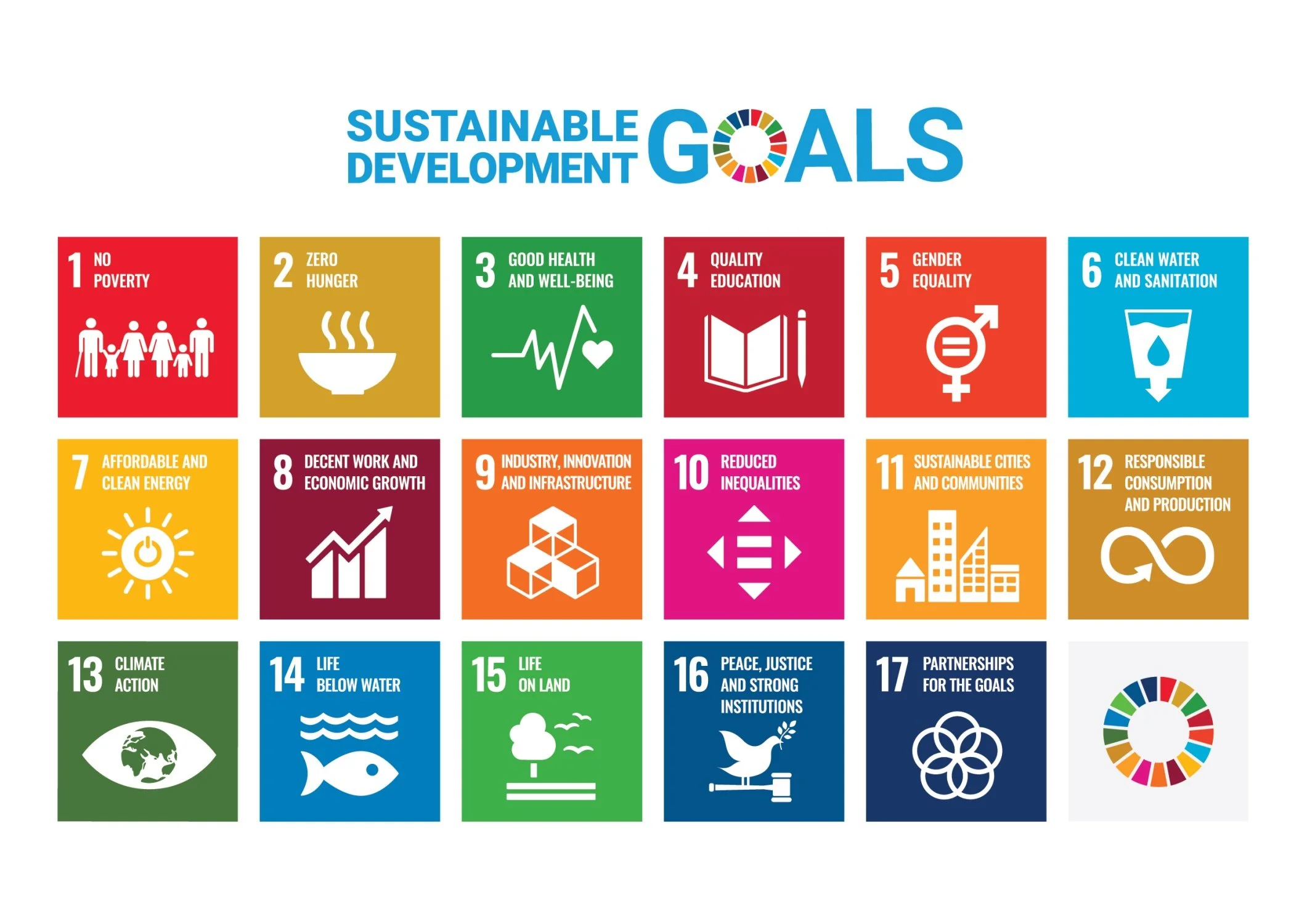

Science and technology are neither good nor bad. In the absence of policy, how and where they are applied and for what purpose is primarily driven by market forces in the global market-based economy. When markets function poorly, or not at all, or are inequitable, science and technology are usually applied highly inefficiently. This is where science and technology policy comes in. Addressing the big wicked problems, the ones the world has agreed are the biggest, such as those embodied in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, requires science to provide a sound basis for acting and technology to address them at the necessary scale. Science and technology policy can underpin focused societal decisions and actions to achieve desired outcomes or goals. I must add that the lack of policy properly informed by science has led to unsustainable development at a global, technology-enabled scale. Finally, how we apply science and technology reflects what we value. We must value nature for its intrinsic or economic value (ecosystem services, to use the economic term). The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review details how poorly we value biodiversity in purely economic terms.

With the support of my wife, Kelly, I returned to school. I completed a Master’s in Science and Technology Policy from George Washington University. Then I worked at the National Academies as a Program Officer, hoping to be a small part of pushing the application of science and technology in a positive direction. The National Academies is one of a handful of institutions focused specifically on Science and Technology Policy. The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy has existed since 1976. There are a few other places focused directly on science and technology policy. But as with most things government policy-related, things move slowly. As one of my mentors once told me, “we put a layer on the snowball that eventually turns into an avalanche and moves the mountain that is government.”

Kelly and I moved with our young son, Thomas, to Seattle, where we had family and where I hoped I could do something that felt more immediately impactful and, if fortunate, would give me a chance to travel. I went to work for Paul Allen, the Microsoft co-founder, and Philanthropist. Paul was part of changing the world through technology. He focused his philanthropy, among several areas, on wildlife conservation, marine and terrestrial. I was extremely fortunate to be part of the initial team focused on that work. What became apparent quickly was how poorly technology was being applied to preserve, protect, and sustain life on the planet. There was a massive opportunity to apply what I had learned about overcoming barriers to technology adoption through sound policy. For the last twelve years and counting, I have had the privilege to work directly on contributing to the goals embodied in Sustainable Development Goals 14 (Life below Water) and 15 (Life on Land).

It was indeed an accident that I became a heartfelt conservationist. Yet, I love it. I have grown to appreciate the natural and wild world disappearing in our lifetime. I am proud to have contributed in some small way to protecting and preserving it through the EarthRanger and Skylight programs, in helping establish Conservation Technology as a field, and in a few other ways. I am deeply humbled by the work of the many people I have had the great privilege to work with. Your dedication to the conservation mission in the face of massive forces working against that mission is awe-inspiring. You are my heroes.

In the photographs and stories on this site, I share some of my experiences with the life and beauty of the tiny little planet that is our home. It’s all we have. I hope we find a way to live on it harmoniously with ourselves and our fellow species.

Hearing from you —